Harun Farocki in collaboration with Antje Ehmann

Reality Would Have to Begin

Curator: Diana Marincu

Exhibition period: 1 – 31 October 2020

Organizers: Art Encounters Foundation, German Cultural Center Timișoara, Timișoara City Hall

With the kind support of: Goethe Institut, Harun Farocki GBR

Institutional partner: n.b.k.

Strategical partner: Timișoara 2021 – European Capital of Culture Association

Co-financers: AFCN, Consiliul Județean Timiș, Casa de Cultură a Municipiului Timișoara

Cultural partners and collaborators: Institutul Cultural Român, BETA

Media partners: Radio România Cultural, The Institute, Observator Cultural, RFI Romania, Aarc – All About Romanian Cinema, Film Menu

The event is part of the Cultural Program for 2020 – Timișoara European Capital of Culture

Harun Farocki (1944–2014) was one of the most important German filmmakers, his impressive body of work including over 100 films. He is known for his unique voice, both related to his experimental approach to the image and the montage, and to the way he formulates critical micro-narratives on history, worldviews and political realities which draw out social practices and phenomena filtered by the use of image and image-making. In his view, the political is closely linked to the visual, especially considering its ability to disclose its own cracks, limits, its instrumentalizations. This creates the tension between visibility and the ability to act as an agent for the institutions that produce and circulate the images.

As a director, screenwriter, author, Farocki created a cinematographic and artistic oeuvre, difficult to frame in a single genre, as it includes documentary film, film essay and video art and media installation, adapted to the variety of topics that he approached. From films made for the German television to feature films screened at major international festivals, later, to installations specifically designed for artistic venues, Farocki’s creation simultaneously maps a self-referential and self-reflexive level of the film, constantly bringing the dialogue between image and image into a close-up. Also, the strategies he used in formulating his own film language established some important concepts: soft-montage, where the author replaces the sequencing with the simultaneity of images which complement, balance or reassess each other; operational images, technical and functional images which serve to define a new visual regime, wherein digital devices and algorithms create images acting outside any human selection ; found footage, existing images that are found and recontextualized, which exude the author’s appetite for research and archiving; digital image, a turn to reassess the visual grammar of the image through a set of new and fluid criteria.

The present exhibition is a selection of Harun Farocki’s films, videos and installations created between 1980s and 2014, part of them in collaboration with the artist and director Antje Ehmann (b. 1968), with whom he’d been working since the early 2000s. The focal point of the exhibition is that it reveals not only the various codes which program and condition the visual field from which the author extracts his images, but also the way in which montage is used as a thinking tool. Montage, as Farocki understood it, often takes the form of linguistic analogies, niches simultaneously dividing the images and bringing them together, indexical gestures, a metaphor for ‘transfer’. The image and the counter image undergo repetition, reassessment, balance, or mutual complement, and the viewer’s imagination infuses them with their coherent political realities.

The title of the exhibition was inspired by Harun Farocki’s 1988 essay of the same title, translated into English in 1992, and which served for the basis of the film Images of the World and the Inscription of War [Bilder der Welt und Inschrift des Krieges]. This title suggests a turning point, a gesture that could bring about a change in an unbearable situation. Specifically, these words are a call to block access to nuclear weapons, and they recall a statement by the philosopher Günther Anders which highlights the failure of the Allies to bomb the access to the Auschwitz camp and to stop further crimes in World War II. To understand what is present but cannot be seen, reality needs to begin.

Acknowledging the two previous exhibitions held in Romania which were dedicated to the German filmmaker (tranzit.ro / Iași, 2018 and Goethe Institut Bukarest, 2019), this exhibition provides several thematic sequences through which one can grasp Harun Farocki’s filmography and artistic activity spanning over an extended period of time with a particular focus on his works already included in the international exhibition circuit. A critical and keen observer of the transformations in society and in the history of the image, Harun Farocki was designated as an ‘artist-archaeologist / allegorist-archivist’ by Thomas Elsaesser, the late film theorist who devoted extensive studies to Farocki’s films. This particular quality of his follows three stages of analysis—detection, documentation, and reconstruction—which always reveal the visual culture’s codes of organization in relation to the power dynamics they mobilize.

A section of this exhibition focuses on multi-channel video installations which make up an ‘archive of filmic expressions’ (as Farocki called it) or a ‘film dictionary’ based on film history excerpts, found footage, and the method of joining up these fragments through soft-montage. What is produced resembles part of a Warburgian iconological project, a space of experimental visual thinking and mapping. The starting point, the two-channel video Interface [Schnittstelle] (1995), is the filmmaker’s most important ars poetica and it represents the turning point in terms of how the ‘image comments upon the image’ and the point at which the writing to the editing meet: ‘I write with images, then I read between them.’ The video installation War Tropes [Tropen des Krieges] (2011) was created together with Antje Ehmann from fragments of known war films, decontextualized and rearranged according to the iconological project showed in the first video—horizontality and simultaneity—and this comes back to one of the leitmotifs in Farocki’s work, the war, which, here, is reconstructed and classified in specific gestures. The short video Synchronisation (2006), co-authored by Antje Ehmann, adds another layer to the question of the signifiers embedded in the film, and the seven-language dubbing of the famous Taxi Driver mirror scene casts doubts over the sincerity of the character’ speech.

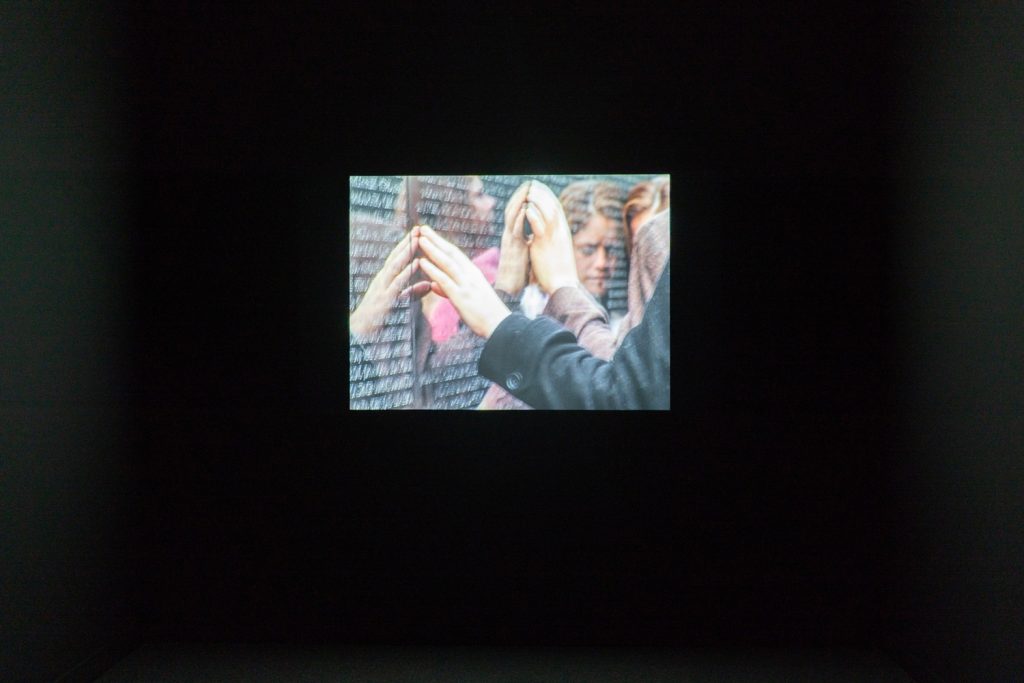

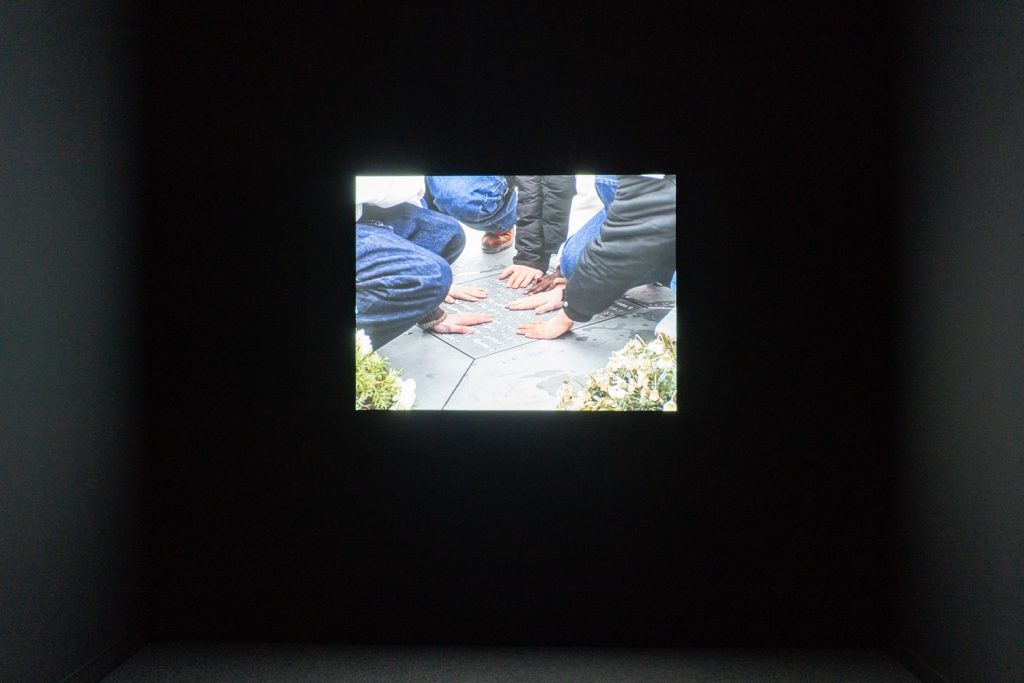

Another section of the exhibition is dedicated to the film essays about the visual history of Nazi concentration camps and the politics of a new visual typology generated by data banks and operative image archives, containing ‘more images than the eye can see’. The failure to understand what was recorded by the surveillance cameras and those of the military’s guided missiles in their fly-overs is shown in the film Images of the World and the Inscription of War (1988) through the wide visual resources which are deciphered by the author in relation to photographs taken by the SS units (images that have to be looked at in spite of our inability to look at them as we should, in spite of all – Georges Didi-Huberman), but also in relation to other cultural references. One of the key elements of the author’s reasoning is camouflage: the makeup of women who advertise beauty products, the veil of the Algerian women, or the water laboratory in Hanover. Aerial military photographs and their scientific filtering through a series of analytical parameters stand in the way of sight despite the amount of information available, turning the observer either into an accomplice or a victim (Christa Blümlinger). In relation to this film-essay, Respite [Aufschub] (2007) starts from black and white footage found by the author, depicting the Westerbork transit camp, originally a camp for refugees from Nazi Germany, which was transformed into a transit and detention camp after Germany occupied the Netherlands. Here Farocki linked the images of the inmates’ daily chores to informational inserts that typically announced the horrors that would follow. As a counterpoint to these two films, Transmission [Übertragung] (2007) is a video that serves as a catalogue of ritual gestures through which the visitors’ hands evoke traces of the history written in the commemorative monuments they visit.

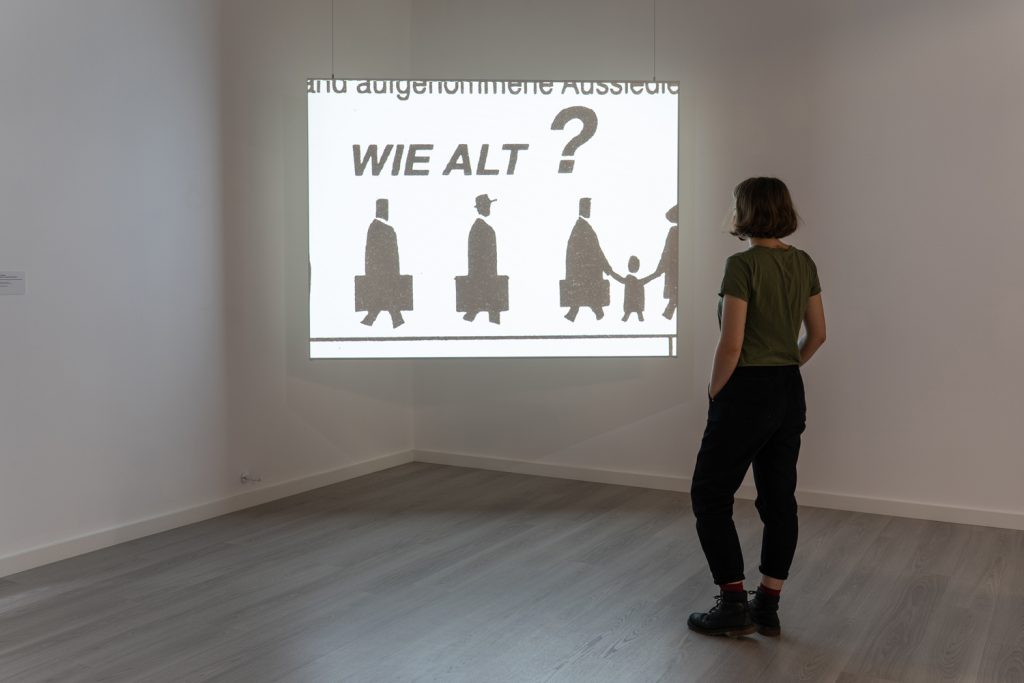

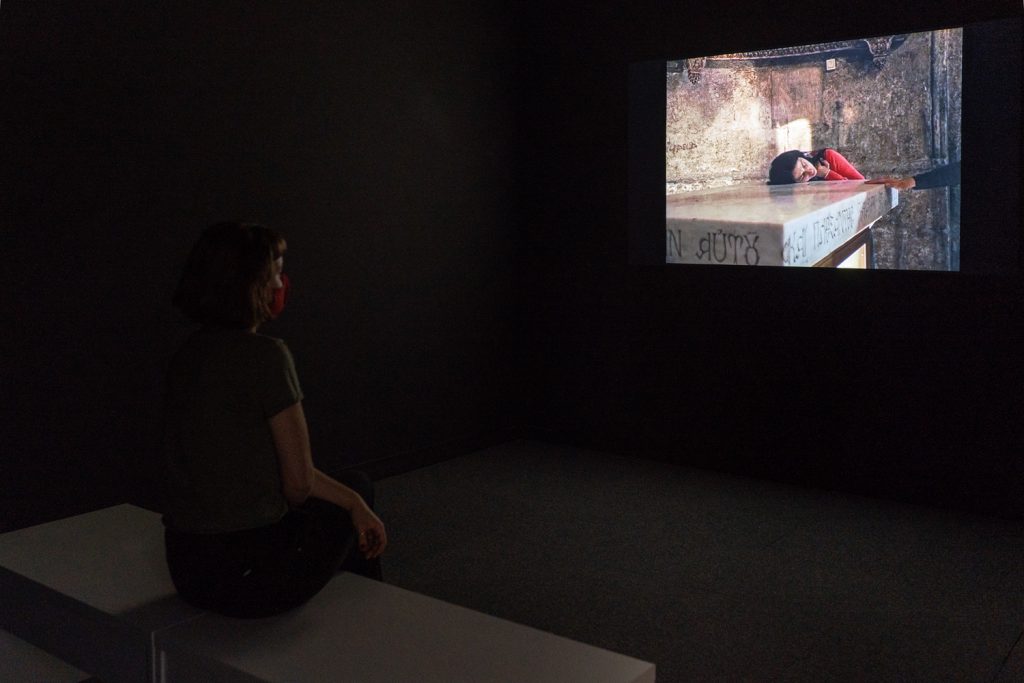

The third thematic section of the exhibition follows another recurrent theme of Farocki’s creation: labor as reflected in the mutations suffered and their valorization or representation in a social-political context. The extensive project which began in 2011 as a co-creation with Antje Ehmann, Labour in a Single Shot, is presented here in a compressed formula of 5 excerpts from the video archive which includes workshops of the two authors in about 20 countries around the world (14 before Harun Farocki’s premature death in 2014, and a few more afterwards). This video series started from observing various, repetitive, often invisible kinds of labor which highlighted both the physical toil and the perception of it, as well as the possibility of weaving a narrative around the accumulation of those 1- to 2-minute uncut filmed sequences. The two authors inquire about what was hidden or even unimaginable in the labor images that they show; which types of labor were mostly found in the city center, and which ones at the outskirts; what was typical to the labor field or, on the contrary, the unusual ones in every city? Another video material, In-Formation [Aufstellung] (2005), approaches the history of migration in Germany and the history of its visual representation in school textbooks, newspapers and other publications, critically filtering out the inability of graphic symbols and charts to represent the migration phenomenon, and to justly reflect the reality.

Technical setup of the exhibition: EIDOTECH

Film and video subtitling in Romanian: Ligia Soare

Special thanks: Marius Babias, director of n.b.k. Berlin, for his kind support during the research period and the organisation of the exhibition; Luis Feduchi, architect, for his contribution in the preparatory stage regarding the spatial arrangement of the exhibition; Mihai Pop, Galeria Plan B Cluj / Berlin, for his help with the technical equipment used for the works Interface and Synchronisation.