The exhibition BRUIAJ is the third episode in the series of collaborations between the artists Michele Bressan, Lea Rasovsky, and Larisa Sitar. Opened on February 28, the exhibition is built around a number of the artists’ recent works and a series of new productions, commissioned for this occasion. We will recreate here the guided tour of the exhibition alongside the artists and the curator Diana Marincu, which took place on February 29. We hope that once we resume our public program and reopen the exhibition, we can also continue the series of guided tours organized over the weekends, dedicated to visitors interested in discovering more details about the works of the artists Michele Bressan, Lea Rasovszky and Larisa Sitar.

Diana Marincu: The starting point of the exhibition was identifying a visible interest of the three artists for an in-depth exploration of memory, whose intricate folds reveal personal histories, mysterious images and turbulent elements which define the artists’ present-day creative laboratory. One of the ambitions of this exhibition was also to ‘test’ new ideas and new works that become clear once they meet the eye of the public. The second proposal that we have launched was to also look at the work of the three artists in the context of the personal bond between them, an artistic friendship that can offer young artists an example of generational solidarity and creative dialogue.

The works reflect the artists’ concern for the relationship between a false antiquity necessary for embedding in collective mythologies, including those of the artistic act, and the updated references to personal landmarks, describing their attitude in relation to the passing of time and to history.

The first part of the space is defined by the presence of several elements evoking, with stunning power, a strange familiarity — the velvet of the curtains that hide two drawings by Lea Rasovsky, the typical pattern of the tiles and upholstery of the armchairs from the ‘90s introduced by Larisa Sitar, a hipnotizing cinema, documented by Michele Bressan.

Diana Marincu: The entire exhibition space was taken over by a collective spatial statement, based on the artists’ interventions in its clear structure and the insertion of some elements that create, here and there, a spectral ambient. The succession of works contributes to the sometimes intimate and familiar, sometimes harsh and abrasive atmosphere of a space outlined by drawings, installations, bas-reliefs and in-situ interventions.

Larisa Sitar: The two armchairs, originally from the ‘90s, where brought here from my parents’ home. Together with the bas-reliefs, they are a reenactment of the household atmosphere of the ‘90s, which used to represent a cheap and, to some extent, decadent luxury, with tiles that imitate marble, velvet armchairs and plaster stucco on the walls. There is a sense of nostalgia here, indeed.

Lea Rasovszky: The Manele music genre was recently banned in the public space in Timisoara and I was reflecting on how could one actually censor such a thing. This fear of a certain type of music says a lot about us; after all, this music is ok, it is an inherent part of the community it represents. In fact, it’s all about whether you accept some things, especially when you’re under the impression that they say something bad about you. We couldn’t help bringing Adi Minune, depicted as a saint. During the Renaissance, people serving the royal court were asked to illustrate saint figures and they did it for the money. Those saints that the believers adored in churches could have been in reality servants or even a courtesan from the village.

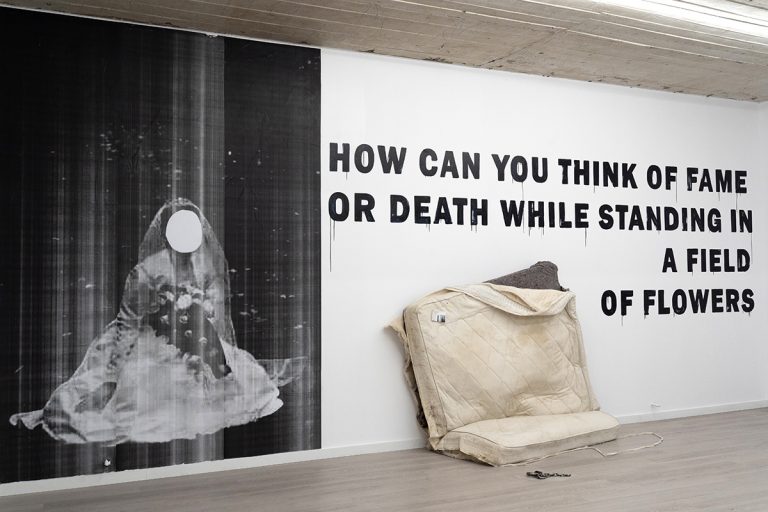

The most contrasting wall in relation to the luxury portrayed by the red and golden velvet and to the domestic ambient is a spontaneous collaboration between Lea and Michele – the wall with the mattress, photo-tapestry and the text how can you think of fame or death while standing in a field of flowers. Here, different types of degradation are displayed — the visual information disappearing in the pixelated image and the object slowly being ruined by time — condense a harsh and violent atmosphere, announcing the total loss of the individual, found also in Larisa’s bas-relief of faceless people.

Michele Bressan: I found the photo on the mattress while looking for an apartment to rent and on the profile of a real estate agent I saw this photo. There was a series. He appeared in all the photos of that apartment, but he had censored his face by scribbling it. It seemed to me that there was a dialogue between my faceless real estate agent, the faceless bride and the mattress. This association came to mind while working on site, through dialogue.

Cinema Patria pictures a sort of a non-space situated at the periphery of perception. Turning his look away from the projection screen, the artist focuses on the chairs in the cinema hall, which are usually ignored, invisible, and tries to capture an image of a place subjected to a continuous transformation and inevitable disappearance. In its proximity, we encounter another element taken out of a story told by Michele Bressan: the work Like in One of My Dreams #2, evoking a different type of absence and an indication of the end, of loss, of death.

The black room marks the far end of the perspective with Lea’s artwork Composition with Wilted Tulips, Racing Pulse and Wooden Cross, next to other drawings and paintings on paper illustrating eccentric male figures, lost, introspective, or tender, all part of the everyday eeriness, but also of the cohabitation with the extravagant and the out-of-ordinary. Everything I Left Behind, a translucent latex leather, can be associated with tangible memories inscribed onto this emphatic surface, another Ego coming from far away, embossed by the elastic fabric of time.

Lea Rasovszky: I like the people that I illustrate. I am interested in these blurry areas. It is a series that I have only recently come to understand, because I have worked on it occasionally over a longer period of time. There are strange episodes, self-portraits, several poses. It is an area that feels comfortable to me. The character made from latex is the one that I drew with my left hand for the work Ode to My Left Hand, which had to be represented in a physical form and which was an experiment for me. I decided to make the character from latex; the stander is another curious happening of the exhibition BRUIAJ; the stander should have been as vertical as possible, like the standers used in tailoring, and the character was supposed to hang on it, but I arrived one morning and I completely wrecked it.

With the ghostly presence of the dress waving in the wind, Michele Bressan’s film Black Dress amplifies the references to the time-erased traces of a body that has left this space.

The black cabinet at the end of the itinerary houses Michele Bressan’s work Like in One of my Dreams #0, the ground zero of his investigations on death and disappearance, a mock-up that catches the point of departure from the space of the everyday life and follows the path leading to a new space, unknown, abstract, made up or desired, the space after death.

Michele Bressan: The scale model is the sequel to another scale model that depicted a funeral, which was exhibited as part of the exhibition PASAJ (2014). I started with the funeral and only afterwards with the first episode, with the hearse departing from the block of flats; I continued on this rather dark vibration, which for me is a curiosity. I refrained from doing photography because that moment has passed, I have found all the answers I needed from photography and now I believe this type of context is better in order to evolve and to challenge yourself, otherwise you stagnate.

Diana Marincu: Among the cores of the exhibition we find a certain investigation on delusion and falsity, of inaccuracy and of the artificial. The disruptive atmosphere of the exhibition interferes with the faked images while intensifying the pulse of fiction disguised as truth. A significant number of the works presented embody this duality and the true-false ambivalence.

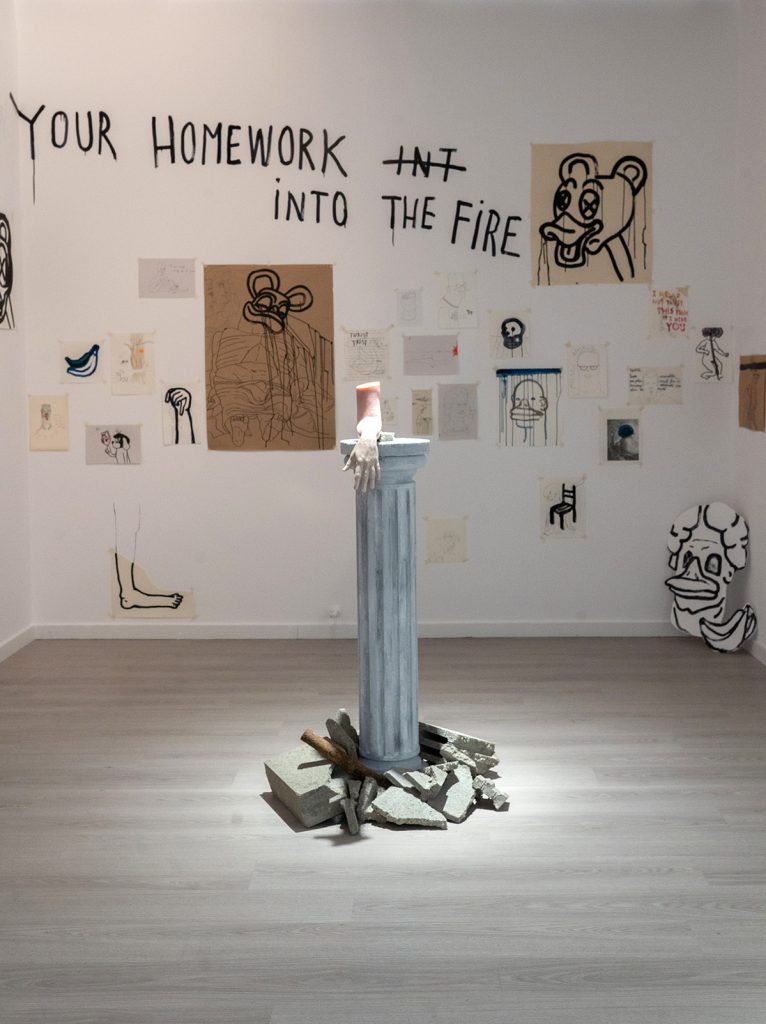

Lea Rasovsky’s studio-room, an ode to the left hand, immerses the viewer in a meditation on error and precision, the left hand becoming the door to a universe only partially controllable, where hazard sets in and academic drawing is superfluous.

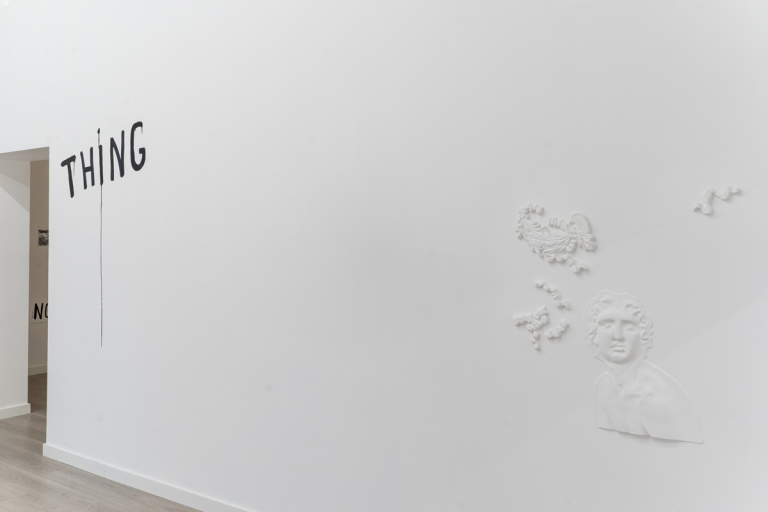

Diana Marincu: The word THING gushes out from Lea Rasovsky’s room; nearby, a male profile, made by Larisa Sitar out of MDF to look like stucco, follows the aesthetic pattern of antiquity; the two drawings made with the left hand by Lea, Nightmare at the Drawing Olympics, bring into discussion the method of drawing taught in school and the pressure to infinitely reproduce the same antique heads and busts, as a form of preparation for the encounter with the real human figure. Following the same line, Larisa Sitar plants a tornado-spiral made of granite in a corner of the room.

Michele Bressan’s assemblage of found objects from Sorrow (fake ancient history) generates a disturbing tension between the softness and the asperity of various materials, from the smoothness of the marble to the sharpness of metal and the warmth of plaster.

Diana Marincu: The last room is serene and nostalgic, visually purifying the memory residues that traverse the whole exhibition. Michele Bressan’s photograph, Timpuri noi, outlines some paradoxes of the city, of Bucharest in this case; it is very hard to precisely identify the exact period of the fragmented object or what type of ruin it is. Ruin and fragment are widely considered an obsession of today’s world, together with a nostalgia whose origins we cannot identify. Things that we try to add a historical significance to; and, in this case, the horse torso could be a fragment from a superb equestrian statue or it could be an imitation. I liked the tension present in the photograph – the idea of falsity and of historical meaning saturated by our desires and nostalgia.

Lea Rasovszky: As for the work Is It Weird That I Want to Taste Your Tears? I was thinking about the act of crying in public, it is something tabu, especially for men. I imagined them in the form of Mexican altars with dry flowers, that last for a very long time but represent something lifeless, dead, that can no longer bloom. It’s an experiment with ceramics, combined with acrylic, not with pigments. They can be brought to life by a simple thing such as water, or an element which becomes dynamic. The glaze will degrade continuously and I will stop them at some point.

Larisa Sitar continues the series of Roboust Boast by associating architectural elements coming from the plebeian language of stucco used by the ordinary to fuel their own longing for the antiquity.

Larisa Sitar: The Roboust Boast series is about the non-western world adopting the classical western architectural decoration style. It has been turned into a social status symbol. After the ‘90s, those plaster decorations, made from polystyrene, that you can now find in any DIY shop, appeared, but it is the same acanthus leaf from ancient Greece.

Overhead Projections, the three fragile images created by Michele Bressan in the last room, add a spectral dimension to the whole arrangement and to art creation in itself. The end of the exhibition is rather sentimental, as Larisa Sitar’s work, in the corner of the entrance, is seen in relation to Michele Bressan’s projections, of a sculptural quality, which take us back to the history of photography and remind us of their transiency.

Michele Bressan: During the making of the RAPI project (Romanian Archaeological Photography Index), I became more interested in the architecture of military fortifications. I made a section of a World War 2 bunker, more exactly of a firing fence. Such bunkers were a limited living space for groups of soldiers deployed there for months. The main site was outlined by a small fence, drawing the boundaries of a continuous landscape. Soldiers serving in such bunkers were often replaced before term, because of severe nervous breakdowns.

The work Bunker was commissioned for the exhibition BRUIAJ and it is placed outdoors, in front of the permanent exhibition space of the Art Encounters Foundation.